Rashomon (1950) 00:01:01

February 10, 2023

Rashomon (1950) 00:01:01

February 10, 2023

André Bazin and Jean Epstein’s Perspective Against Cinema, Reality, and Rashomon (1950)

The relationship between art and reality is one of representation and mediation. Cinema is a unique form of art that is a combination of many individuals and art forms, such as directors, actors, the audience, photography, lighting, editing, set design, or acting. These aspects of cinema result in many replications of types of representation and lend themselves to many more metaphorical interpretations. Cinema represents a culmination of the way art can represent reality, which both André Bazin and Jean Epstein build upon in different ways in their essays. However, they do differ slightly on the specifics of the way in which cinema and photography represent reality. Bazin and Epstein discuss how photography and cinema represent reality in their essays “The Ontology of The Photographic Image” and “The Intelligence of a Machine,” respectively, which can be explored through examples in Akira Kurosawa’s classic masterpiece Rashomon (1950).

Rashomon (1950) 00:02:44

Rashomon (1950) 00:02:44

Bazin describes the relationship between photography and reality as “the first time an image of the world is formed automatically, without the creative intervention of man” (Bazin, 63). Bazin argues that photography, and thus sequentially cinema, represents and recreates the world as matter-of-fact and with a “quality of credibility” not achieved by other art forms, which ultimately are other attempts of recreating reality (63; 62). The mind does not need to make a lapse in judgment or suspension of belief to understand and accept what is captured by a camera lens and shown in a photo or film is something real and tangible. The camera not only shows things that do actually exist, but it shows them in perfect dimensions, so there is no stretch of the imagination needed to understand what an audience is viewing. Bazin also argues that in the way photography captures actual realities’ qualities and dimensions, cinema represents and demonstrates the “change of time” captured in its length (64). Cinema recreates the function of time in reality, or the movement, decay, or growth of the camera’s subject across a film or shot’s length (64). Sometimes this change may be small, such as a few moments of a plant’s lifetime in a single shot, or even recreate large lifelong changes such as character growth, aging, or even death across multiple shots, scenes, or acts.

Rashomon (1950) 00:16:13

Rashomon (1950) 00:16:13

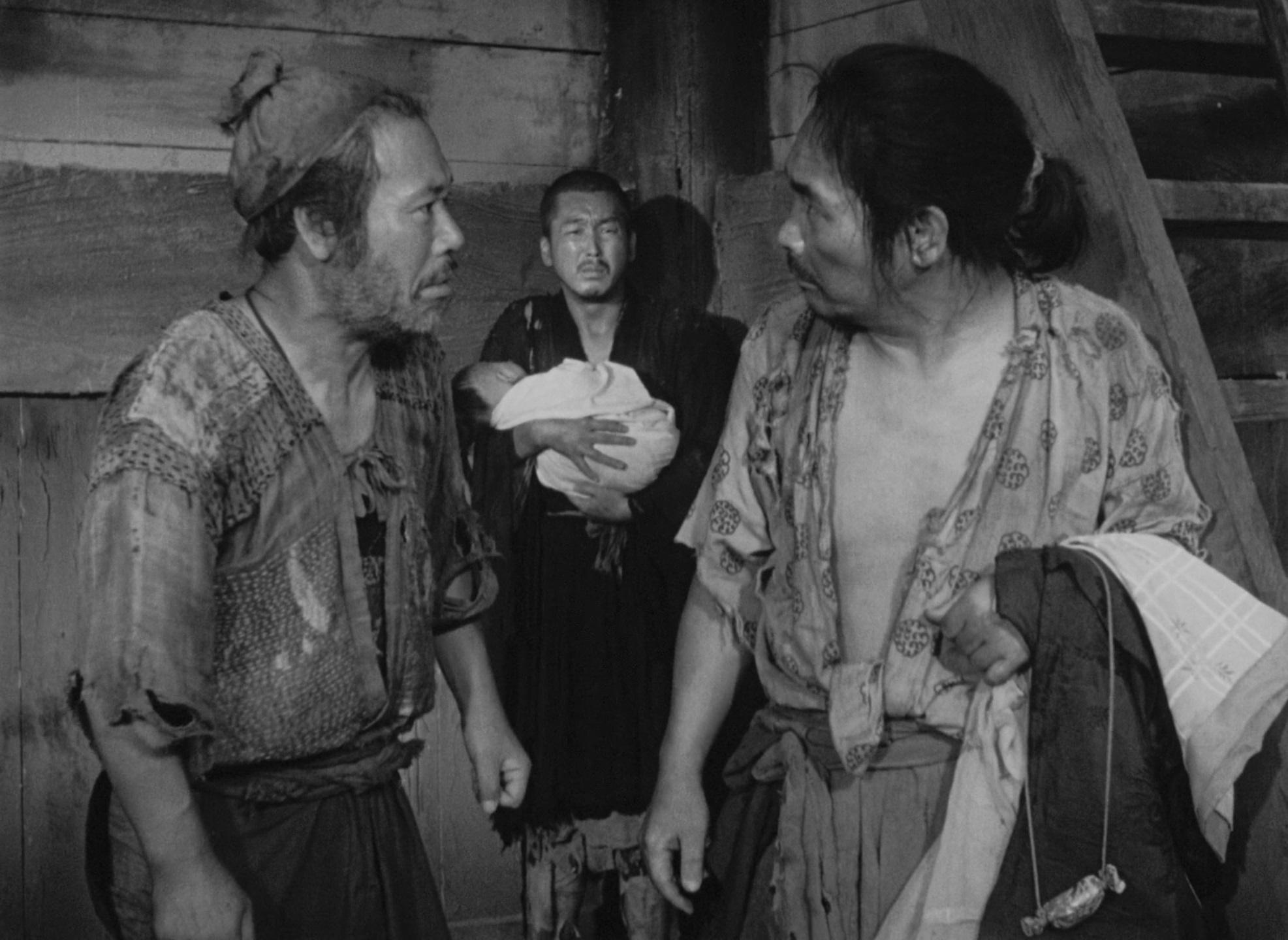

Examples of this type of direct representation Bazin describes within the film Rashomon can be seen in the “realness” of the rain and the swords the audience sees through the film, as well as the revealing of the true character of the woodcutter (Takashi Shimura) by the end of the narrative. The audience never has to question the credibility of the torrential rain at the shrine the three men are huddled away from while they discuss their tales, there are entire shots lent to just the task of viewing the rainfall, adding to the rain’s realism (Rashomon, 00:02:32-00:02:52). The rain is even given more validity when it makes the woodcutter and commoner (Kichijiro Ueda) visibly soaked while they fight over the kimono and locket in the shot at 01:22:37-01:22:51. In a similar way, during the first sword fight between the samurai (Masayuki Mori) and the bandit (Toshiro Mifune) at 00:33:07-00:35:40, the swords are displayed as sharp and deadly, the sword fight as authentic, the consequences genuine, and the danger is palpable through the scene. There is not even a need by Kurosawa to dedicate a specific shot to the “realness” of the swords, the cinematic form implies it by design. By the end of the film more of the nature of the woodcutter’s character is revealed through what we see and are shown by the film, in the same manner as spending time with someone and seeing them in different situations will tell one more of another’s “true” character and motivations. The audience does not and would not need to question what they are seeing according to Bazin’s description of the automatic encapsulating of nature or representation of reality by the camera.

Rashomon (1950) 00:38:32

Rashomon (1950) 00:38:32

Epstein, on the other hand, outlines the relationship between cinema and reality by writing that cinema recreates the human experience of perceiving reality through limited or “discontinuitous” senses (Epstein, 72). In the same way cinema artificially creates motion from its still frames, the human senses of sight and touch creates a sense of solid objects, and physical phenomena. Epstein explains this in the example of when “an electron microscope extracts a few snapshots” of an electron, that the image “offers no more real signification” of the true nature, only a part of a whole (73). The microscope “fix[es] them in time,” not within, or of, their natural nature (73). Within the mind the subconscious creates order and fills in gaps that the human senses leave incomplete or undecipherable. The mind perceives the cinema as continuous motion, and a metal rod feels like a solid smooth object, despite the film being a collection of still frames and the iron molecules being rigid and consisting of mostly “empty” spaces between each molecule, and even between the atom’s subatomic particles.

Rashomon (1950) 00:54:07

Rashomon (1950) 00:54:07

Examples of Epstein’s explanation of the paradoxical representation of the misrepresentation of reality to humans through cinema can be seen in Rashomon’s fragmentation of the film’s flow of time, and through the theme of the nature of storytelling being deceptive. While Rashomon presents itself as a single unified film, it can be viewed as actually five separate shorter films, one of each by the bandit (1) at 00:16:19-00:37:18, the wife (Machiko Kyo) (2) at 00:39:42-00:49:39, the samurai (3) at 00:51:35-01:01:56, and the woodcutter (4) at 01:04:41-01:19:20, as well as the scenes in between of the three men at the shrine (5) from start to end. Like Epstein’s broken glass pane analogy, however, when “all five” of the “films” are assembled in Rashomon, they represent something entirely unified as a whole entity together (73). The whole is entirely separate and more complex than they could ever ascend to alone (73). Albeit metaphorically, the theme of Rashomon on the deceptive nature of storytelling (narrative cinema), being told to the audience as straightforward truth each time the setup begins again before the court, represents Epstein’s view of the perceived continuity of a reality of discontinuity (00:12:17-00:16:19; 00:38:42-00:41:15; 00:51:35-00:52:47; 01:01:57-01:04:41). Epstein hypothesizes within this metaphor that the “cinematograph” is replicating the function of the human mind, or recreating the beginning of the process of thought (76). Just as each time one watches a series of still frames flipping at a particular rate as cinematic art, one perceives motion, or each time the metal rod is felt, it feels solid, so too does Rashomon “tell” the four accounts as entirely true, and within the mise-en-scene is indiscernible from the physical reality it is portraying.

Rashomon (1950) 01:16:22

Rashomon (1950) 01:16:22

Though Bazin and Epstein both describe the relationship between cinema and reality as one of representation, they disagree on how this occurs. Bazin argues what is captured by a camera lens and shown in a photo or film is something real and tangible, while Epstein supposes the cinematograph’s mechanism of discontinuity appearing as continuity represents the same ways humans interact with reality. Through an analysis of the cinematic elements of Rashomon, its narrative devices, and its structure, both philosophers’ arguments can be explicated and substantiated.

Rashomon (1950) 01:21:45

Rashomon (1950) 01:21:45

Bazin, André. “The Ontology of the Photographic Image.” Translated by Hugh Grey, Westfall, pp. 61-65.

Epstein, Jean. “The Intelligence of a Machine.” Translated by Christophe Wall-Romana, Westfall, pp. 70-77.

Rashomon. Directed by Akira Kurosawa, performances by Toshiro Mifune, Machiko Kyo, and Takashi Shimura, Criterion, Dairi Film, 1950.

Westfall, Joseph, editor. The Continental Philosophy of Film Reader. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018. ISBN 1474275737.

Chandler Murray

e:Murrayc15@gator.uhd.edu