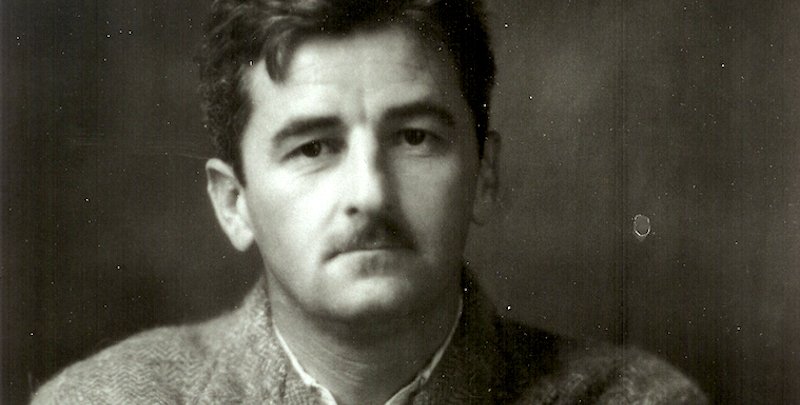

A young William Faulkner -credit and rights to lithub.com/young-william-faulkner-in-the-french-quarter/

May 10, 2023

A young William Faulkner -credit and rights to lithub.com/young-william-faulkner-in-the-french-quarter/

May 10, 2023

The Shaded Isolation of Emily and Narrative Suspense in “A Rose for Emily”

The short story “A Rose for Emily”, written by William Faulkner follows the isolated life of Emily Grierson in a southern American town during the period of reconstruction. The plot begins with Emily’s death and then alternates between events in her life to obscure the truth behind her actions and circumstances. The incorporation of the elements and themes of Southern Gothic literature into the story facilitates suspense throughout the narrative and complicates Miss Emily’s life and personality. The short story is narrated in the third person to strengthen the distance and mystery around Emily’s character, thus building suspense. These elements create an anticipation for the reveal at the end of the text, while portraying Emily as a sympathetic, grotesque, isolated, and enigmatic character. By the end of the story, Emily emerges as a realistic character with conflicting motivations and actions. Emily’s relationship with her father and isolation from the rest of the community are key factors in understanding her characterization. The literary elements used in “A Rose for Emily,” such as the Southern Gothic themes, broken chronology, and third person narrator, collaborate to complicate and obscure Emily’s character, which produces narrative suspense and emphasizes the effects of isolation on her life.

The Southern Gothic themes, such as, the aging town and characters, morally questionable events, decaying Grierson house, and ostracized characters like Emily and Homer, add to the suspense and unease throughout the story. "A Rose for Emily" takes place in the southern town of Jefferson sometime around 1860-1900, spanning across the seventy years of Emily’s life. The setting and time period highlight the fractured social framework of racial tensions, chauvinistic femininity, and economic downturn that are reflected in the narrative and characters, especially Emily. This setting is crucial to the Southern Gothic theme of the text, as well as the depiction of the sublimity and civility with which the narrator and townspeople approach Emily. The townspeople say, "poor Emily" and "will you accuse a lady to her face of smelling bad", having a sort of reverence for her character while still looking down upon her (Faulkner 317, 316). The distance in which the townspeople interact with Emily, across the street and behind closed doors, isolates her from the town, while keeping her a spectacle for gossip. Susan V. Donaldson writes in their article, “Making a Spectacle: Welty, Faulkner, and Southern Gothic,” about the cliches and themes associated with women in Southern Gothic literature. Donaldson writes about the conflicting portrayals of Emily and examines her among Faulkner’s other women characters as “Confined in their stories and subject to the scrutiny and sometimes brutality of other characters, their communities, and even their readers” (572). Emily’s isolation is one of the Southern Gothic elements itself, not just a product of the other elements. To Donaldson, Emily’s “spectacle” and isolation creates the theme writing, “they face ritualistic punishment… we watch them being punished… for not being the southern women they are supposed to be” (572). Although most of Emily’s life is constructed for her by her father, because she does not marry and socialize like the townspeople, they ostracize her. Both the narrator and the townspeople approach Emily in a way that undermines her autonomy as a woman, distances her because of her social class, and yet still treats her with a level of outward respect due to customs surrounding adult women. Emily’s occupation as a second-class member of the community is revealed when the men break into Emily’s house to spray lime for the overwhelming smell and when the townspeople gossip about her being lonely instead of helping or interacting with her. The narrator says, “when she got to be thirty and was still single, we were not pleased exactly, but vindicated,” proving they never expected to accept her into their social circles (Faulkner 316). Her position in the community is established as being both an outcast and someone to observe or control under the guise of protecting her. The reader can only be thrust from one “crisis” to another while the stakes, disturbing nature, and mystery surrounding Emily construct the suspense and complexity of the text (Watkins 509).

The elements of Southern Gothic literature obscures Emily’s character while isolating her through the unnerving themes of the genre. The narrator and townspeople find Emily’s lack of romantic life unusual, which makes her an outcast in the town. Moreover, Emily’s actions, such as sleeping with Homer’s corpse, reveal just how incompatible with society her isolation has made her. Emily’s existence as a social pariah and being economically destitute, imprisons her within her home for most of her life, both as a child and an adult. As Donaldson writes, the dynamics of southern culture, such as the shame the townspeople impose on Emily against her sense of pride, “evoke the kind of imprisonment for women often associated with the gothic” (572). The text also contains violent aspects in the final act, revealing that Emily poisoned Homer, and through deliberate word choice when the men break into the boarded-up room. As Faulkner details, “The violence of breaking down the door seemed to fill the room with pervading dust” (320). The overall Southern Gothic setting of the town is constructed in part by Faulkner’s careful characterization of the townspeople and their actions. The street Emily lives on is described as “encroached and obliterated” (Faulkner 314). Her house is detailed to have a “stubborn and coquettish decay” (Faulkner 314). Emily is isolated in a town of isolation, like “an eyesore among eyesores,” in which her house is described (Faulkner 314). The unsettling themes of the Southern Gothic genre in “A Rose for Emily” build narrative suspense as the truth becomes more questionable and unnerving with each act.

“A Rose for Emily” utilizes a non-linear structure, providing important events of Emily's life in flashbacks and flashforwards throughout the narrative, which leads to a multi-faceted depiction of her character. This structure and characterization support the well-developed round character of Emily, who is written in a sympathetic light despite her disturbing actions revealed in the final act. Menakhem Perry in their article "Literary Dynamics," describes a product of such a chronological structure as "retrospective repatterning" (Perry 60). When plot details are arranged out of order and change how the previous events would have been received, retrospective repatterning occurs. The rearranging and reinterpreting of objects and meanings of events within "A Rose for Emily" creates narrative suspense. For example, the conclusion the townspeople’s gossip creates about Emily after buying the arsenic, saying “She will kill herself,” is delegitimized when she survives (Faulkner 318). When Homer’s demise in the final paragraph is revealed, the truth “that was hitherto considered stable turns out to be only temporary” (Perry 60). This approach serves to encourage or convince the reader to draw different conclusions about Emily before the end of the text. The break in chronological order of the narrative in “A Rose for Emily” plants direct conclusions about Emily throughout her life in the reader, reserving the truth about her damning secret for the last moment while building suspense throughout. With the story beginning with the narrator attending the funeral of Emily, she becomes isolated and separated in another layer from the audience, townspeople, and events of the narrative. Whatever revelations or knowledge that may be learned through the text will have no effect on Emily’s life.

The audience is unable to fully understand Emily's character due to the broken chronology and her isolation from the events in the narrative, which in turn obscures important plot details that heighten the narrative suspense. The reader is unsure what to consider true between each of the contradictory conclusions and observations made by the narrator. The narrator’s opinion of Emily differs from “respectful affection for a fallen monument,” to contradicting that saying, “the Griersons held themselves a little too high for what they were” (Faulkner 314, 316). The narrator describes her physical appearance as “Bloated,” or “tragic and serene” at different times in the narrative (Faulkner 315, 316). Additionally, the narrator adds more contradictions by describing how the townspeople “could pity Miss Emily” after her father’s death (Faulkner 316). Then they resentfully called her “a disgrace to the town and a bad example” after her open romance with Homer less than two years later (Faulkner 318). These depictions and observations of Emily are not only conflicting but presented to the reader out of time and chronological order. By presenting the different characterizations of Emily out of order, Faulkner blends each new shade of Emily into one another, constructing her true character.

The third-person point of view narrator is another layer of the text’s cryptic and uncertain method of storytelling, as the reader is swept from one observation and interpretation of Emily to the next. Emily’s character is obscured by almost entirely being presented to the reader through third-person observations. Emily only speaks on two different accounts in the short story, during the tax visit, and when she buys arsenic at the end of act 1 and act 3, respectively (Faulkner 315, 317). The use of the narrator to inform the reader about Emily’s choices and motivations complicates her character, while solidifying her isolation from the town and audience. Emily’s path and actions are textually not her own to make but are channeled by the narrator and townspeople. Zijiao Song’s article, "Transitivity Analysis of A Rose for Emily,” systematically dissects the short story to analyze its word choice and narrative components. Song examines the effect the narrator and townspeople have on the depiction of Emily’s character writing, “People seem omniscient and everything is within their mind. But actually they are wrong, Emily has already poisoned Homer… the things they know are [their] subjective imagination” (2294). The narrator complicates and shades the character of Miss Emily by providing contradictory information and skewed perspectives. After the narrator reveals Homer is homosexual and will not marry Emily, despite being so confident that “she will persuade him yet”, the townspeople again settle for a half-hearted “poor Emily” (Faulkner 318). The narrator is “a little disappointed” Emily and Homer do not have a public performance of their imaginary union, despite ostracizing the pair anytime they are in public (318). In the next paragraph, when Emily and Homer begin to publicly ride around in the “glittering buggy”, the narrator and townspeople contradict themselves again by deriding them as “a disgrace to the town and a bad example to the young people” (318). In the final paragraphs of the text, the narrator is fixated with revealing what is in Miss Emily’s boarded up room, just as they were fixated on Emily’s life and actions. The words and social stigma the narrator and townspeople spread about Emily perpetuates her isolation and loneliness. The narrator creates the conditions of Emily’s life to later gawk at and criticize. Song concludes that “they are the main killer of Emily’s love” (Song 2294). Their romance is poisoned by the social condemnation of the town, making Emily’s story a complicated tragedy in which she is defiant, a victim, and a perpetrator. The words of the narrator and townspeople, despite being unreliable and subjective judgmental opinion, dictate Emily’s actual life and social conditions. How she is perceived by the narrator affects how she is treated by the townspeople, and ultimately the outcome of her romance with Homer. In a way, the narrator dictates Emily’s life due to the amount of pressure and control the townspeople’s gossip has on Emily’s actions and isolation. Song writes, “Their words become big obstacle[s] of Emily’s love” (2294). The narrator and townspeople ultimately nurture Emily’s isolation to unhealthy heights. The social stigma of her aristocratic background, pickiness with men, Homer’s homosexuality, and their pre-marital relationship all constrain the number of possible choices Emily feels she can take. When Emily’s father passes away, “the house was all that was left to her” (Faulkner 316). They constrain her autonomy to do anything about it other than recede into the only property she has, her inherited father’s home.

The effects of Emily’s isolation are highlighted to the reader, depicting Emily as a complex, realistic character with multiple dimensions. The literary elements in “A Rose for Emily”, such as the themes of Southern Gothic literature, the disrupted chronology, and unreliable narrator each paint a detailed image of Emily. Like actual humans, Emily acts in contradictory ways with conflicting motivations, such as killing Homer and wanting to be with him or resenting her father for isolating her while not wanting to let his body go to the funeral home. Emily’s complex and realistic character allows for multiple possible interpretations and conclusions about what goal the short story has according to its narrative components. However, each interpretation and conclusion are each heavily influenced by Emily’s isolation. For example, Jack Scherting’s article "Emily Grierson's Oedipus Complex” uses a psychoanalytic approach to explore Emily’s relationship with her father and Homer. Scherting argues that her father’s strict control over Emily is a metaphor for being married to him, whom she replaces with Homer, and eventually his corpse when the townspeople condemn their romance (404). Emily is unable to preserve the way of life she had developed with her father and subsequently Homer, so she is compelled to “deny progress and commit murder” (Scherting 405). Scherting arrives at a conclusion that Emily represents an “element of Southern society which attempted to protect itself through isolation…Unable to confront the realities of life” (405). The realities of Emily’s economic situation, sheltered upbringing, social isolation and suppressed desire for intimacy are too much for Emily to navigate through alone. Emily’s pride from her family’s name, cultivated by her father, perpetuates the converging problems that eventually cause her to make rash, irrational decisions. When she isolates herself away from the town, murders Homer, and preserves her love with Homer’s body over the latter half of her life, she is making calculated decisions of self-preservation. Her exact motivations and reasoning behind her actions is not revealed in the text, but instead are arranged so that it is left up for interpretation. The suspense that is created by the mystery of Emily Grierson’s character extends past the final paragraph of the text, to linger in the mind of the reader. Just as the suspense of the narrative can never truly dissipate, Emily’s isolation continues past the narrative and her death. Emily’s isolation is eerily permanent and her motivations are unresolved in a similar disenchanted manner.

Emily’s isolation deteriorates her mental and physical condition, which cyclically makes her isolate herself more and more into her home. The literary themes of the Southern Gothic genre, the alienating narrator, and Emily’s placement out of time bring the effects and conditions of her isolation to the forefront. In the text, the narrator brings up Emily’s aristocratic heritage, saying “She carried her head high enough” and southern customs on femininity, her “noblesse oblige” to further propel her into deeper seclusion (Faulkner 317). The judgmental and prying townspeople in “A Rose for Emily” work to complicate feelings of pity or compassion the reader will develop for Emily. The narrator metaphorically constructs in the reader the same damaging notions the townspeople have for her. All the literary components work to inflict distance and biased judgement onto Emily’s character, to reflect the social isolation and judgment that Emily experienced in her life. Song writes “Her behavior seems abnormal but it can be understood as her helpless struggle” (2295) The text characterizes Emily’s decisions as ones made out of desperation as her life choices dwindle in number. While her decisions are made out of desperation, her seclusion has left her with little control over her future and happiness. The suspense and worry the reader has for Emily work alongside the tension and isolation her character navigates, to humanize her misery.

The literary elements of “A Rose for Emily” alongside the effects and actions caused by Emily’s isolation build suspense, from beginning to end. Emily’s funeral isolates her character from the onset, placing the reader’s perception behind a narrator that both resents and is fascinated with her. The Southern Gothic theme of macabre subject matters and the decaying town veiled by a veneer of civility, facilitates the unease and tension of the text’s suspenseful building of mystery and intrigue. The narrative suspense accumulates as the audience jumps from interpreting Emily as a grotesque monster, a tragic villain, a sheltered and manipulated individual trapped by her father, or a lonely and mentally unwell person. Floyd C. Watkins writes in their article “The Structure of ‘A Rose for Emily’” that Faulkner “divided the story into five parts and based them on incidents of isolation and intrusion” (509). Beginning with the “special meeting of the Board of Alderman,” the townspeople interrupt Emily’s solitude to collect her taxes and subsequently intensifies her isolation by doing so each time they visit her home (Faulkner 314; Watkins 509). Emily’s isolation increases, obscuring and complicating her character as suspense builds into the final act of the story. Emily’s isolation is proportionally related to the narrative suspense and mystery. Watkins writes “Each visit by her antagonists is… a contributing element to the excellent suspense in the story… she withdraws more and more until her own death” (509). As the townspeople become more and more interested in Emily, their civility becomes more intrusive. When Emily finally has some connection and social life with homer, “the minister’s wife wrote to Miss Emily’s relation in Alabama,” causing her cousins to visit and frustrate her progress (Faulkner 318). Just as some of the tension and suspense is being relieved, the narrator and townspeople force Emily’s relationship to end. The suspense regains its momentum as Emily begins her final drastic path to a permanent state of isolation and buys the arsenic. Watkins describes Emily’s isolation as something that is highest at the beginning and end of the text, which mimics the flow of the suspense in the narrative (510). The narrative suspense and Emily’s isolation is almost alleviated due to her relationship with Homer in the third act, only to tragically and thematically be reinstated as their relationship is sabotaged by the townspeople, her cousins, and Emily herself. The story ends moments after the funeral scene where it begins, as the men barely, “waited until Miss Emily was decently in the ground,” before opening the boarded-up room where Homer is entombed (Faulkner 320). The carefully crafted components of the story converge in the final moments; the disjointed chronology straightens, the narrator fades into first person, and the Southern Gothic horror is revealed plainly. The reader is left to contemplate the permanently isolated character of Emily and the grim actions she enacted as a consequence of her loneliness. Faulkner seeps the story’s suspense into the foreground of this final scene, and as an afterthought to contemplate thereafter.

The application of literary elements like Southern Gothic themes, a broken chronology, and a third-person narrator, in William Faulkner’s "A Rose for Emily" constructs a complicated and ambiguous portrait of Emily, while heightening suspense and stressing the significance of her isolation. When asked in an interview about the meaning of the title, Faulkner insinuates the story itself is “’A Rose for Emily’ —that’s all” (1033). The short story acts as a token of reverence to the tragic life of Emily, like a rose you would leave on a grave or a eulogy spoken at a funeral. Despite the depravity Emily ultimately inflicts upon Homer and the insanity she is driven to, Faulkner wants the reader to focus on the tragedy of her tale and the social isolation that precipitates it. Emily is a product of her environment, first under the sheltered watch of her father, and then under the judgmental study of the townspeople. Her actions can be interpreted as being caused by the social paradigm she is faced with throughout her life. “A Rose for Emily” contemplates who is responsible when societal forces seclude a member from their communities. The text questions who is responsible or should be punished in turn for crimes that result from cultural persecution. The short story leaves Emily, the perpetrator and victim, to suffer in solitude, yet allowed to live out her life in destitution and disgrace.

Donaldson, Susan V. “Making a Spectacle: Welty, Faulkner, and Southern Gothic.” The Mississippi Quarterly, vol. 50, no. 4, 1997, pp. 567–84. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26476897. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Faulkner, William. “A Rose for Emily.” The Story and Its Writer: An Introduction to Short Fiction, edited by Ann Charters, Bedford/St. Martins, 2019, pp. 314-320. ISBN 1319105602.

Faulkner, William. “The Meaning of ‘A Rose for Emily’” The Story and Its Writer: An Introduction to Short Fiction, edited by Ann Charters, Bedford/St. Martins, 2019, pp. 1033-1034. ISBN 1319105602.

Perry, Menakhem. “Literary Dynamics: How the Order of a Text Creates Its Meanings [With an Analysis of Faulkner’s ‘A Rose for Emily’].” Poetics Today, vol. 1, no. 1/2, 1979, pp. 35–361. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1772040. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Scherting, Jack. "Emily Grierson's Oedipus Complex: Motif, Motive, and Meaning in Faulkner's "A Rose for Emily"." Studies in Short Fiction, vol. 17, no. 4, 1980, pp. 397. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/emily-griersons-oedipus-complex-motif-motive/docview/1297937150/se-2. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Song, Zijiao. "Transitivity Analysis of A Rose for Emily." Theory and Practice in Language Studies, vol. 3, no. 12, 2013, pp. 2291-2295. https://www.academypublication.com/issues/past/tpls/vol03/12/20.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Watkins, Floyd C. “The Structure of ‘A Rose for Emily.’” Modern Language Notes, vol. 69, no. 7, 1954, pp. 508–10. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3039622. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Chandler Murray

e:Murrayc15@gator.uhd.edu